IMANI explains why Agyapa deal is bad for Ghana

Why the CSOs Oppose the “Current” Agyapa Deal

August 27th, 2020

Summary

- The timeline of 4 months to IPO is problematic, unless the Government has surreptitiously filed for listing. To ensure favourable pricing of the offered securities, the timeline for listing any MIIF SPV on any international exchange should be extended to at least April 2021. This should also allow additional scrutiny into the Agyapa transaction because, so far, it lacks the basic minimum of transparency and assurance of above-board dealing required of a sovereign transaction.

- The degree of information-hiding has been so intense that, per the official record, it took the Ministry of Finance more than a year to share the full set of agreements with the Government’s own Attorney General following an initial request for legal review in January 2019. Unsurprisingly, the final agreement ratified by Parliament defies many pieces of advice offered by the Attorney General, including a suggestion that the Investment Agreement be limited to a fixed term of 30 years.

- Raising short-term capital and building a solid company to invest Ghana’s royalties are not intertwined objectives and the selected vehicle for listing securities on the LSE Main Market is ineffective for achieving either strategy in a holistic way. The massive upfront costs of listing and sustaining a listing is equivalent to borrowing at over 10% per annum, far above Ghana’s current sovereign borrowing rate.

- There is a case to be made for diversifying the country’s sovereign wealth strategy and acquiring some geo-economic influence, but that should not be pursued at the high cost of valuing 75% of all of Ghana’s future royalties at 30% of their true value. The $1 billion valuation of these massive resource entitlements is unconscionable and amounts to undervaluing Ghana’s resources by over 65%.

- Less than 25% of future royalties should go for that amount of money in any such transaction. Our position is backed by a review of several such “royalty streaming” transactions around the world. A private market transaction would be superior to a public listing in this regard.

- The claim that dividends shall prove a seamless substitute for royalties in the future is abjectly wrong in view of typical dividend yields in the context under evaluation and the fact that the transactions expressly exclude dividend protections granted the government by the SIGA law.

Short Essay

The Government of Ghana has given a number of reasons why it prefers to assign its rights to receive royalties from the country’s gold mines to an independently run Ghanaian entity (“ARG”) controlled by another, overseas-registered, entity in the tax haven of Jersey, which it hopes to have admitted to the Main Market of the London Stock Exchange (LSE) via a standard listing.

We disagree with most of the reasons given to justify the decision so far and wish to urge the government to be more open to better and deeper scrutiny of the whole affair.

In this short note, we shall lay out as clearly as we can why after a thorough review of the Agyapa deal by a multidisciplinary team we commissioned, IMANI has decided to join an assortment of leading Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) to publicly express misgivings about the deal.

Timeline to Fundraising

The government has indicated that it sees the Agyapa deal as a means to raise both short-term capital, through proceeds from an upcoming IPO of the overseas-incorporated entity (“Agyapa”), and long-term resources from the country’s gold assets through dividends earned from its shares in Agyapa.

Neither of these two strategies add up. For an entity with no trading history and capitalised solely with contractual entitlements to future revenues from Africa-based assets, it is expected that the due diligence review by the Listing Transactions unit of the Financial Conduct Authority and the bevy of advisors needed to pull this off shall be excruciatingly long-winding.

It is important to recall that the government aborted a listing before December 2019 and again around March of this year because, according to well-briefed sources, it could not assure dealmakers of the robustness of the royalty payment arrangements. From the evidence we have seen, the Finance Ministry spent months ignoring advice that Parliamentary approval was needed as it was in a hurry to list. After much fumbling around, they have finally obtained Parliamentary approval.

Far more conventional entities have in the past taken as long as 12 months to complete listing on the LSE Main Market. The 31st December timeline in the government’s current plans is thus problematic if indeed it is true that the listing process has not already commenced and was awaiting clearance from Parliament.

The relationship agreement between the Jersey-incorporated vehicle (Agyapa Royalties – “Agyapa”) that the Government wants to use to raise funds on the LSE, and the local vehicle to which it is assigning its rights to receive royalties from the mines (Agyapa Royalties Ghana – “ARG”) actually expires by the 31st December deadline if a listing on the London bourse has not happened. This is a strange arrangement.

Why 31st December? Why is the government always in a rush? Does it keep fumbling because of this rush? For a planned listing that so far has no publicised prospectus, no clarity as to the existence of an underwriting agreement, no PR plan in place as far as anyone can tell, and for which even basic draft longform reports from accountants have reportedly not been prepared, why would a Government set 4 months to undertake the incredibly complex task of engineering a good offer price and attracting bountiful subscription of the offered shares? When questions were asked about audited accounts of the non-trading Agyapa vehicles, once again, reviewers were met with stonewalling.

Unless, there is a plan to rush through the process, agree to a low offer price and depress market valuation to benefit institutional investors who can then grab the country’s future royalties today for cheap, IMANI cannot fathom why after more than a year of fumbling, the process is being rushed again.

Our first demand therefore is that the relationship agreement should be amended. The deadline should be changed to April 2021, at the earliest, and the Government should plan for a process of due diligence, sponsorship and underwriting negotiations, and public relations concurrently and sequentially lasting at least 9 months with a view to getting the best offer price and subscription levels possible for this overseas investment vehicle. This is just our first suggestion.

It does not, however, mean that we agree with the overall structure of the deal. In fact, we mostly disagree. We believe that substantial surgery needs to be performed on the overall anatomy of the planned privatisation of government’s royalty stake in the gold mines. In subsequent passages we shall explain why.

READ ALSO:

Agyapa Royalties deal 'unconscionable' - Attorney General

Short-term Capital Raising

The standard tool for valuation in most economic contexts, and certainly in respect of securities, is benchmarking. To determine whether or not Ghana is getting a fair deal from Agyapa, we must look at three main benchmarking factors: movements in the price of gold, movements in gold production volume, and movements in prices of gold-related assets in public and private markets.

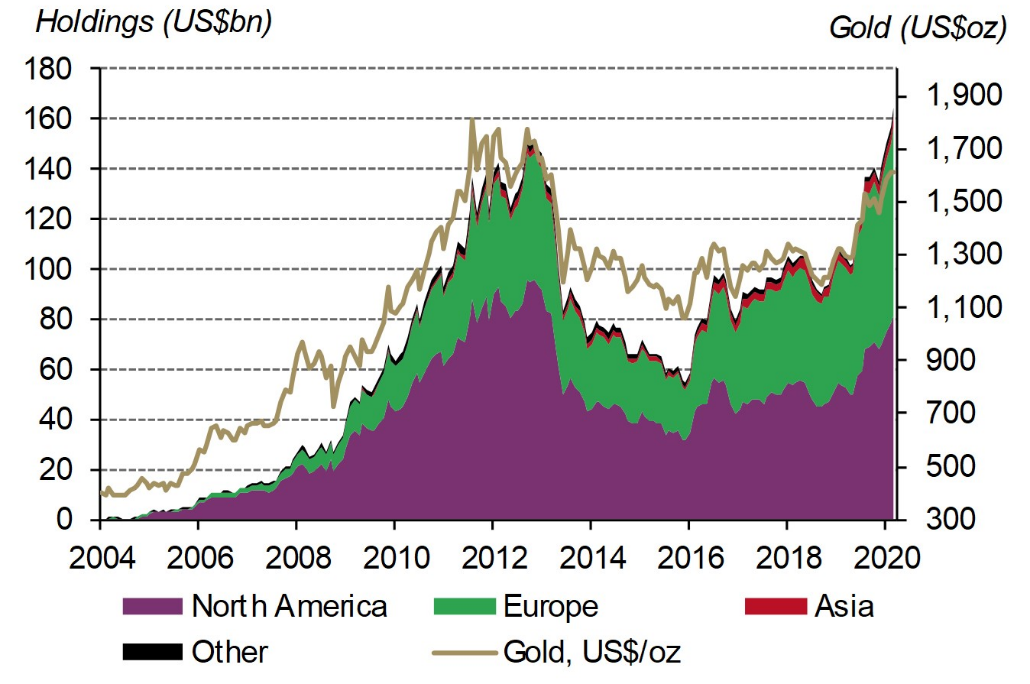

Exchange-traded funds that have gold as the underlying asset are a rigorous benchmark for getting a feel of the market’s attitude to gold-pricing shifts. Below we present Bloomberg data that shows that the slackening in global economic performance has led to improved prospects for gold pricing.

Historical Gold Price Dynamics (Source: Adam Perlaky, with data from Bloomberg and the World Gold Council).

The bullish sentiment on gold as a commodity is undoubtedly a durable trend for the near-term and medium-term horizon.

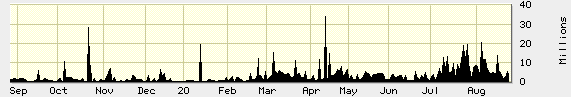

Stock performance of AIM-listed Pan African Resources (Source: Superperformance.com and BigCharts.com)

On the other hand, recent upsurges in the performance of gold stocks exposed to African production, such as Pan African Resources Plc (PAR), belies considerable volatility.

PAR is very interesting for the kind of analysis we are engaged in because its revenues are roughly similar to Agyapa’s prospective earnings. It is exposed to underlying assets similar to Agyapa’s though its direct control of those assets reduces its risk profile. It also has two decades of trading history. Currently, it trades at a market cap of just a little over $600 million.

When we look at other listed entities with revenues tied to underlying gold income streams that have features familiar to the Agyapa situation, we get a similar price-earnings ratio (PER) picture. It is worth bearing in mind that there are too few pure “royalty streaming companies” of Agyapa’s calibre to permit an analysis without broadening the peer cohort, as we have done by including PAR.

In short, the anticipated market cap of $1 billion for Agyapa is highly optimistic, insofar as the Government intends to use the public markets for valuing the royalty income streams, raising further concern about the government’s calculations regarding this IPO-based royalties streaming transaction structure as a short-term fundraising option.

Whilst there aren’t many pure gold royalties streaming companies with their assets predominantly based in Africa that can be used for pound for pound comparison, gold royalty streaming as a transaction model is quite mundane in the international capital markets.

Since Franco-Nevada started the practice in 1986, hundreds of companies have cropped up that will buy rights to royalties directly from asset holders and package the rights in various shapes and sizes for further trading.

Entities with revenues very similar to Agyapa’s prospective earnings are Altius and Maverix, both based in Canada, whose market cap dynamics reinforce the picture we have painted earlier about the unfavourableness of the public markets for the type of frontloading transaction Ghana is pursuing.

In the private markets, on the other hand, things look very different. In several transactions we have reviewed, where far lower revenues than Agyapa’s anticipated streams were involved, the valuation prospects look considerably better than the “$1 billion or less” target Agyapa is likely to hit.

We examined many deal structures in the public markets in comparison with the private markets. But in the interest of time and space, we urge the reader to consider just two: the ill-fated Triple Flag IPO, aborted around the same time that Ghana first attempted to list Agyapa[i], and the gold portion of the Wheaton – Calda Gold Marmato private market transaction, where the royalties streaming major purchased 6.5% of royalty streams of the Marmato asset for $110 million[ii]. Head to head analyses of transactions like these overwhelmingly support our thesis of superior private market valuation and the undervaluing of Ghana’s royalty assets in the public listing option.

Clearly, thorough benchmarking analysis of equities listed on international public exchanges shows the need for special effort on the part of the government to obtain a favourable IPO price.

But it raises a more fundamental point: if the point is to raise short-term money: the convoluted path of going through an IPO is completely unnecessary.

The government can sell a smaller percentage of future revenues over a defined time-period to any one of a hundred royalty streams companies at a discounted rate. Private market transactions in this respect, as we have already indicated, are cheaper, quicker, and more likely to yield a better valuation in the current context.

Going this route would afford government of Ghana more time to pursue the longer-term strategic goal of diversifying the investment options available to it by setting up an overseas vehicle to pursue royalty streaming assets in other markets as it has expressed an interest in doing. It is noteworthy to note, however, that the MIIF Act restricts SPVs like Agyapa to equity plays only, without the option to invest in debt securities. This restriction further weakens the use of a listed vehicle as a cashflow cow, something the government needs for fiscal headroom purposes.

To repeat for emphasis: the two goals of short-term fund-raising and longer-term investment diversification are completely separate and, quite frankly, unrelated.

Reading through the Government’s justifications for pushing forward with Agyapa, the case for intertwining these two objectives (of raising money quickly “off the books” and setting up a vehicle to better invest the country’s royalties) come across as very weak. Because the PER benchmarking of the value of the country’s future royalty streams discounts the amount at a higher rate (by more than 65% per our calculation) than what Royalty Streams companies like Franco-Nevada typically use (less than 40% judging by the trend in current transactions), the use of the stock market listing approach to raise short-term money ends up being very expensive, and from our national perspective, a rip-off.

Worse than all this, the intertwining strategy has led to a structure that puts Ghana’s sovereign interests at considerable risk.

The dividend yield of many equities similar to Agyapa’s on similar bourses have been less than one percent over long cycles. In fact, in a recent index computation, the gold asset leveraging company (among large caps) with the best average dividend yield was AngloGold Ashanti at a measly 0.76%. Newmont scraped in at 0.39%. The Government’s own Merrill Lynch – led analysis shows weak dividend yields across many prospective peers in the royalty streaming category.

Anglo Pacific Group PLC, the only royalty streaming company on the London main bourse, which, admittedly has struggled of late, does have a dividend yield of 7.69% but it comes at a weak PER of just over 5%, imperilling the more valuable capital gains opportunity.

Anglo Pacific Group Share Price Performance (Source: MorningStar)

Dividends Are No Comfort

Even at a market cap, in the Government’s optimistic scenario, of $1 billion, a 1% yield per annum amounts to less than $10 million in dividend payouts, IF Directors vote to declare dividends.

Very rarely do countries tie their sovereign wealth yields to dividends. Frankly, it is almost unheard of for a sovereign wealth strategy. If dividends were an important source of revenue, the country’s 10% equity interest in gold concessions in Ghana managed by 10 international companies (excluding Newmont and Anglogold), many of them with parents listed on top bourses would already be generating significant revenues.

As the government has persistently complained, however, it does not make any significant dividends/equity interest revenue from these carried interest stakes.

In 2018, for instance, the Government’s 1.56% in the global AngloGold Ashanti structure yielded just a little above $300,000. The year before it was about $575,000. Intriguingly, the normal dividend protections the Government may enjoy under extant law have been ousted by a curious decision to remove all applicability of the State Interests & Governance Authority (SIGA) Act to these Agyapa transactions in a bizarre process that we recount later in this essay.

Capital gains, as hinted above, are the proper targets for structures like Agyapa, but even a reliance on capital gains raises other worrying concerns that we can only delve into when we examine the legal structure of the Agyapa transaction.

All this beg the question of why the government would not simply utilise local, non-listed, vehicles of the Minerals Income Investment Fund for the more long-term objectives of the strategy. Unless there is some official desire to pay large amounts of money to expensive British and local consultants, why will the country spend over $40 million to raise $500 million? Why shouldn’t the Government simply cut down the wide latitude for political interference in MIIF so that it can exercise its various investment mandates?

Note that the average cost for listing a low-premium structure such as Agyapa on the LSE Main Market is in the region of 10% of funds raised. This amounts to an effective interest rate of 10% for an implied instrument with a life of 1 year. This, for a country that borrows at less than 6.5% on instruments with a 6-year life.

Besides these considerable upfront costs, there is also the high costs of keeping companies listed on the stock market, a phenomenon that partly accounts for the ongoing desertion of the public markets by many of the fastest growing companies in the world[iii].

Nevertheless, to fully grasp the extent of Agyapa’s incoherence, one must examine the legal architecture.

The Deal Structure

There are four key agreements governing the transaction: an agreement that erects a Chinese wall between the Minerals Income Investment Fund (MIIF) and the Agyapa entities; an agreement that redirects 75.6% of all royalties from virtually all gold producing mines in the country from MIIF to Agyapa (leaving 2% for salaries and the like); an agreement that formalises Bank of Ghana’s role as a custodian bank for holding the royalties until they can be safely sent to Agyapa in USD; and a fourth agreement that seeks to leverage Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA’s) powers to collect the royalties from the mines for Agyapa. There are other agreements that do things like indemnify transaction advisors and prospective sponsors, like investment banks, but they are not very critical.

Separately, the MIIF law was also amended to free up Agyapa and potentially other SPVs from some of the disclosure and regulatory strictures of the country’s public finance and state enterprise ownership statutes.

Despite having set up Agyapa in November 2019, not a single document opening up this major strategic policy shift has ever been published explaining the rationale until the recent controversy. In fact, the first time many keen observers of the Ghanaian scene, including IMANI, got to know about the full details was when the minority in Parliament “rebelled” against the attempt to speed up passage of the transaction documents above. To date, none of the key documents that constitute this “Project Kingdom” strategy, as the Ministry of Finance calls it, are on the Ministry’s website or accessible to the public through official channels. IMANI and the CSOs have had to rely on contacts in Parliament to obtain copies of the agreements after the controversy broke.

Apparently, the certificate of urgency meant to expedite the parliamentary evaluation of the investment/assignment agreement in days rather than weeks was necessitated by the Attorney General Department refusing to go along with an earlier draft despite protracted negotiations. This is why an entity set up in November 2019, which had been the subject of many months of considerable disagreement even within the government, needed to be ratified in haste, in barely 24 hours in fact, on 14th August 2020.

The MIIF set up the Agyapa SPV in the British Crown Dependency of Jersey so that this entity can assume ownership of a Ghanaian incorporated entity called Agyapa Royalties Ghana Ltd. The former Irish CFO of Dangote Cement was engaged to handle finance and a politically connected Ghanaian placed at the helm as CEO. The Ministry insists that Korn Ferry (reported in the Ghanaian press variously as “Conferi” and “Kornferry”) was hired and given free rein to professionally head-hunt the management and Directors of the company.

Considering that Korn Ferry did not advertise this role (we have not been able to find a public advertisement despite an intense search) and no list of directors and managers of Agyapa are still publicly available, we have to take the Ministry’s word for it that somehow a global search for talent (even if the emphasis was on Ghanaian talent) that literally no one heard of somehow ended up determining that the son of a high-ranking Ghanaian official is the best qualified candidate for this asset management job.

Yet, the Ministry saw no need to publicise this outstanding coup. The public found out only because the notice page of a transaction agreement sent to Parliament ten months after the appointment was made happened to leak. In the circumstances, we are compelled to share the perception held by many people that the manner in which Agyapa was staffed is shady. But that is the least of our concerns.

In recent press statements and comments, the Ministry of Finance has stated that only 12 mines and 4 “development assets” are affected by the Agyapa deal. This cannot be correct since the agreement clearly indicates that as many as 48 mining leases, including prospecting leases (concessions on which production is yet to start) are impacted by the agreement. This means that not only are current producing assets locked into this arrangement, even assets whose returns are not yet clear have been allocated as well.

Furthermore, the Ministry’s position that the Agyapa entitlement is restricted to the life of each of these mining leases is not borne out by the agreement, which clearly foresees the possibilities of lease extensions, renewals, successions and replacements.

To all intents and purposes, and by the sheer operation of Euler’s number, the entitlements are best considered, as we have done in this essay, “perpetuities”.

Moreover, the wording of clause 3.4 (Optional Mining Leases) can easily be construed to imply a “right of first refusal” to take over additional mining assets not currently included in the agreement. This clause clearly states that before the MIIF can sell royalty streams in any other mining asset, besides the ones assigned to Agyapa, it must provide up to 90 days latitude to Agyapa to make an offer and negotiate terms for that mining asset.

By allowing considerable flexibility in construing the prospective flows into the SPV from existing and future mining leases (described as “converted mining leases” in the Investment Agreement), and removing any possibility of a financial cap, the government has seriously shortchanged the Republic.

In clause 6 of the Investment Agreement, the government is vicariously banned from revoking mining leases or terminating their ownership, to the extent that such an action would cause the reversion of the asset back to the ownership of the state, if that lease is part of the allocation granted to Agyapa in the transaction. Thus, without investing any of the billions that multiple mining companies have invested to justify their stabilisation and development agreements, a royalties agreement has been used by Agyapa to grant stability rights to virtually all gold-producing mines in the country solely for the benefit of Agyapa.

By virtue of strict terms in the Relationship Agreement among the Republic of Ghana and the Agyapa entities, Agyapa retains the right to sell more than 51% of its ordinary shares to investors if the IPO is oversubscribed. The continued claim therefore that majority control by Ghana is cast in stone is incorrect.

The very idea of “majority control”, in its traditional sense, is eschewed by the Relationship Agreement through numerous provisions, such as clause 3 of the Agreement wherein the Government is proscribed from attempting to prevent the appointment of Independent Directors it does not like, or to remove them if already appointed. A broad provision in clause 3.2 actually requires that Directors representing Ghana recuse themselves from deliberations where Ghana may have a “conflict of interest”.

Virtually all critical decisions to be taken by Agyapa must pass by a majority of Independent Directors, not the entire board. That is to say, without recourse to the wishes of the Republic’s representatives on the Board. Such decisions include material changes to constitutive legal documents, appointment of and engagement with auditors, disputes with Ghana over royalties allocations, bank account operations, and determinations about the impact of Ghanaian laws on the stability clauses of the Agreement.

At any rate, the Republic, through the MIIF, is only definitely entitled to two Directors. Appointing a second Director may however warrant a majority of the Independent Directors to increase the number of such Directors in order to dilute the influence of the additional Government of Ghana representative. Agyapa’s Independent Directors can decide, per section 5 of the Relationship Agreement, to replace the Government representatives if, to their mind, the continued presence of that Director may lead to some unspecified regulatory non-compliance.

In short, the Relationship Agreement is cleverly structured such that the investors who buy the shares of Agyapa following the IPO in London can circumvent policies favouring Ghana’s national interest if such policies do not align with the share price maximisation goals of traditional investors. To expect that a vehicle structured this way can become part of some kind of Ghana-determined industrialisation strategy whether in the mining sector or elsewhere is be naïve about the reality of modern shareholder interests.

A Problematic History

Government records do not paint a very favourable picture of the arrangements put in place by the Finance Ministry to realise the goals of the Agyapa strategy.

According to paragraph 2 of a letter from the Attorney General to the Finance Ministry dated 28th May, 2020, and referenced as D54/SF.239, the Government commenced the processes of assigning mineral royalties to Agyapa as far back as January 2019 when a draft Relationship Agreement was presented to the Attorney General (AG) for review and advice.

This is highly problematic because the official record also establishes an incorporation date of November 2019 for Agyapa. The implication therefore is that at least ten months before the incorporation of the vehicle, the Ministry of Finance was already trying to secure approval for the assignation of royalties to a non-incorporated entity. Luckily, this attempt was rebuffed.

The second attempt came in March 2020 when the Finance Ministry brought back a second draft of the Relationship Agreement for the AG’s legal review. Even at this point, the Finance Ministry was still refusing to share the subsidiary instruments of the Relationship Agreement with the AG’s Office. More strangely yet, even the main Investment Agreement, in which most of the key terms could be found, was not submitted to the AG’s Office for review. Why? Luckily, once again, the AG stood its grounds and insisted on seeing these critical documents.

But these manoeuvres to hide information contributed mightily to the long doldrums in which the whole transaction has languished for many months now, leading to the unseemly rush today.

The original Relationship Agreement had been drafted such that nearly all new discoveries of minerals from which the Government might move to allocate royalties to an SPV would have become subject to a near-default assignment to Agyapa because of a ridiculously stringent “right of first refusal”, a clear instrument of potential blackmail. Luckily, the AG slashed the time period during which these pre-emption rights might be exercised. Unfortunately, what remains of them is still capable of being wielded to extort the Government.

We maintain that there should have been no pre-emption rights at all to allow such potential arm-twisting in the future.

Despite strong concerns in the AG’s office about the provisions of the various agreements, many of them unresolved even today, a memorandum to the President for Executive Approval of the Arrangements dated the 18th of June 2020 still lamented a “delay” in the listing of Agyapa on the LSE in January 2020 and talked up an “overdue” upcoming listing on the same bourse in July 2020. Quite clearly, the attitude of the government’s chief financial advisors at that time was to marginalise its own AG.

In the aforesaid memorandum, the Finance Ministry goes into some provisions of the Public Financial Management (PFM) Act and Regulations, such as the requirement of prior approval by the Finance Ministry of annual financial plans of entities subject to the Act, which it believes would be constraining for SPVs incorporated by the MIIF if maintained. Curiously, the Ministry does not ask for specific sections of the Act to stop applying to SPVs. Instead, it requested for the entire Act and its regulations to be emasculated where MIIF SPVs are concerned. Same for the State Interests and Governance Authority Act.

To be very clear, there is nothing wrong with provisions in the PFM and SIGA Acts that deal with reporting and accountability (such as sections 77 and 95 of the PFM Act and sections 29 and 32 of the SIGA Act, as well as regulations that flow from them). An SPV that is capitalised primarily with public money remains, regardless of fancy nomenclature, a “state-owned enterprise” and should thus be subject to the same accountability rules as any other majority state-owned enterprises and joint ventures. In many parts of the world, sovereign wealth vehicles are subject to public scrutiny standards.

It is completely contradictory for the promoters of Agyapa to tout the high disclosure standards of the LSE Main Market whilst, at the same time, complaining about public scrutiny standards in the country whose resources are bankrolling the whole Agyapa enterprise. It is worse when they defy clear advice to subject the disclosure terms of the Agreements to Ghana’s Right to Information Act.

Notwithstanding all these issues and the efforts by the AG to restrain some of the excesses, Cabinet Approval had already been sought and given in 24th March 2020 to remove application of the PFM and SIGA Acts; and to sign the Indemnity Deed for the transaction bankers as well as the Relationship Agreement. The reader may recall that as late as 5th August 2020, the AG continued to express misgivings about the Relationship Agreement.

In fact, in a letter dated July 22nd, 2020, and also referenced D54/SF.239, the Attorney General, clearly frustrated by the continued side-lining of their advice, minces no words in highlighting how nefarious to the interests of the Republic the whole arrangement is. The provisions in the various agreements are described as onerous, unconscionable, and “skewed against the interests of the [MIIF] and Ghana”; whilst the benefits are dismissed as unclear.

Many of the terms and provisions of the Relationship and Investment Agreements complained of by the AG were never properly amended. This include important comments such as a requirement for a fixed 30-year tenure; the treatment of incidental costs, such as insurance premia, as potential losses; the distortion of pre-existing stabilisation agreements (clause 2.2 and clause 6 of the Assignment/Investment Agreement); and weak reciprocity. The same can be said for somewhat minor guidance offered by the AG and blatantly defied, such as the removal of “judicial acts” as species of “Law” given the existence of more appropriate sub-definitions such as “judgments” and “orders”; and the joint liability of the MIIF and the Republic of Ghana despite the former being a body corporate in its own right.

So, how was it that despite such a contentious misalignment between the Government’s chief legal advisors and its chief financial advisors, stretching over a year per the official record; despite at least four months of intense correspondence between the two Ministries; and several, important, outstanding issues, the Attorney General finally provided clearance on 12th August, 2020, paving the way for the laying of the final drafts of the Agreements in Parliament on the 13th of August, 2020, under a certificate of emergency, still riddled with errors (incorporated reference to an unpassed Act and persistent reference to a non-disclosed entity called, “Ghana Gold”) and the shocking rubber-stamping of the documents in less than 24 hours?

Luckily, the Record provides the answer. The Attorney General lost their nerve.

According to the last trails of correspondence between them, the AG met the Finance Minister on 10th of August, 2020. The latter had sent a letter pleading for expediency on the 11th of August, 2020. The next day, the AG suddenly forgot about several contentious matters, raised some peripheral issues in a final letter, and brought the sad, miserable, saga to a close.

The Valuation Problem

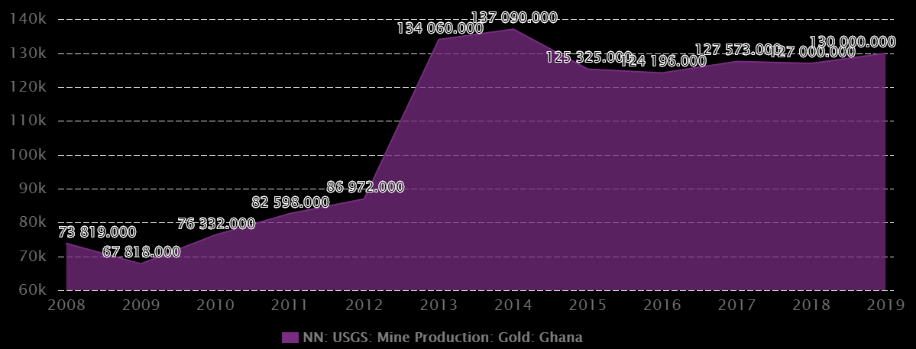

As Ghana inches towards a new gold production plateau of 150 tonnes, and the global geopolitical environment makes a medium-term price average above $2000 highly realistic, the decision to sell all the country’s future entitlements to receive royalties from gold for $1 billion becomes very hard to sustain.

Ghana’s gold production new plateau (Source: USGS & CEIC)

Whilst commodity price forecasting is far from a science, there is a growing consensus that this is a breakout moment for gold. A view shared by the usually thoughtful analysts at the Economic Forecast Agency who have joined many analysts in predicting a multi-year support/resistance for gold of $2400 for most of the current decade. But even if we were minded to moderate this forecast to $2200 or even $2000, we shall be talking about annual earnings of more than 40% higher than the just-ended 5-year period.

In estimating the present value of Ghana’s royalty streams and therefore fair value for Agyapa, we are talking about a growing perpetuity, not just a perpetuity (even ignoring the prospects of lease renewals, the operations of Euler’s Number in finance renders income discounting from a stream lasting more than 25 years effectively a perpetuity in most types of analyses). Growth implies that the discount rate needs shaving.

If risks of potential default is taken into account (the NDC flagbearer has threatened to terminate the deal in a future NDC government), and accommodation made for various volatilities, a discount rate of 7.5% would be reasonable. But this is partly offset by the growth in production and prices estimated in the coming decade. Some analysts have accommodated the sliding scale royalty rates negotiated by the likes of Newmont, AngloGold Ashanti and Goldfields, whereby these companies pay less than the 5% rate that their compatriots pay if gold prices stay below certain thresholds.

If our theory that average gold prices shall be supported above the $2000 mark for the most part of this decade holds, then we can simplify the analysis by using the 5% royalty figure since the sliding scale does not apply when gold prices breach the $2000 mark.

We can further simplify the sums by using an average production volume in Ghana of 5 million ounces of Gold, instead of the roughly 5.4 million ounces “on average” figure that most analysts accept. Approaching the sums this way yields long-term royalties of roughly $250 million per year. Discounting the growing perpetuity then yields a present value for the royalty streams of $5.5 billion. Even if the discount rate is increased from 7.5% to 9% (on account of greater price and production volatility) and the growth rate dropped to 2%, the present value of the Ghanaian state’s royalty entitlements amounts to a cool $3.57 billion. 75% of that amount is in excess of $2.68 billion. Any valuation therefore that leads to a valuation of less than $2.5 billion is unconscionable, to borrow a term used by the Attorney General to describe an earlier version of the Agyapa Assignment Agreement.

Our recommendation in this respect is therefore that unless the offer price can yield an IPO valuation of $2.5 billion, the exercise is wholly unwarranted.

We would, in fact, counsel an alternative strategy of assigning 25% of the country’s royalty streams to a vehicle if it could raise $1 billion on a reputable exchange purely to pursue geoeconomic maneuvering and investment diversification objectives. Our sense however is that the best valuation is likely to be obtained in the private markets.

But be that as it may, the proposed Agyapa transactional structure as a means to both raise short-term capital and to maximise the annual proceeds from gold in the longer term is problematic, for neither objective is favourably realizable from an SPV listed on the London Main Market within the bounds of the government’s current strategy.

[i] Please see, for instance: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-tripleflag-ipo/elliott-backed-triple-flag-scraps-ipo-signals-tough-2020-for-listings-idUSKBN1YF1T9

[ii] See, for instance: https://www.kitco.com/news/2020-06-22/Caldas-Gold-Wheaton-announce-planned-streaming-deal-for-Marmato-project.html

[iii] See, for instance: https://www.sharesmagazine.co.uk/article/london-suffers-a-sharp-decline-in-the-number-of-ipos

SOURCE: IMANI Ghana